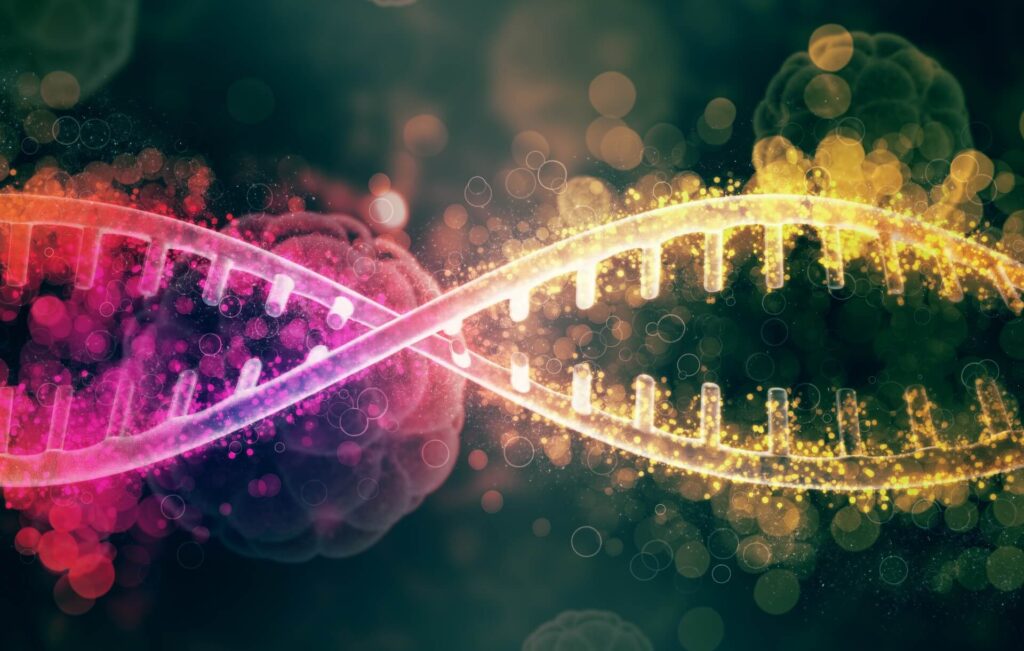

In 2018, a Chinese scientist named He Jiankui shocked the world by announcing the birth of the world’s first gene-edited babies, twin girls Lulu and Nana. Using a powerful procedure called CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing, he had attempted to edit their genomes with the intent of producing babies who would be resistant to HIV. This news made headlines across the globe just hours before The Second International Human Genome Editing Summit in Hong Kong, not because it was a major breakthrough, but because it crossed a line that many believed science was not yet ready to cross, that of human germline genome editing of embryos.

As a high school student with a growing interest in genetics and biotechnology, I wanted to revisit the events that unfolded in 2018 and understand: What exactly happened? Why was this experiment considered so controversial? And most importantly, what lessons can we, as the next generation of scientists, and thinkers learn from it? The intent of this article is therefore to understand and communicate the responsibility that comes with scientific endeavours. My personal endeavour is to do so with the humility of one who knows his place not as an expert but as a science student.

CRISPR’d babies

I came across this term in Henry Greely’s article with the same name in the Journal of Law and Biosciences, which I have referenced and suggest it for further detailed reading. In his article, he explains the “He Jiankui affair.”

CRISPR is a gene-editing tool that allows scientists to make precise changes to DNA. Originally discovered as part of a bacterial defence system, it has now become a powerful technique used in medicine, agriculture, and research.

He Jiankui claimed to have used CRISPR to disable both alleles of a gene called CCR5 in embryos, aiming to produce babies who were immune to HIV. The virus invades cells by attaching to a protein coded by the CCR5 gene. A small subset of people who are immune to HIV carry a natural mutation of this gene that blocks the virus from attaching to cells. He attempted to recreate this mutation using CRISPR in embryos. These embryos were then implanted into a woman’s uterus, and the twin girls were born. This was a clear case of DNA editing in germline cells.

Human germline editing refers to changes made to the DNA of embryos, eggs, or sperm in a way that the edits are passed down to future generations. Unlike gene therapies that treat a person’s existing cells, germline editing alters the target genes before birth, preventing inherited diseases, but it also raises serious ethical concerns about altering traits that affect not just that individual, but their subsequent generations.

At first glance, helping children avoid a deadly disease might sound noble. But the deeper I read, the more I began to see why this was a huge ethical and scientific issue.

The Trouble

Technically, Gene editing in human embryos carries major risks. CRISPR can make changes in the DNA that were initially not intended or targeted, called “off-target” effects. It can also affect only some cells in the body, a condition known as mosaicism, and therefore the final outcome can be unpredictable. In this case, the babies didn’t receive the exact mutation found naturally in some people that offers protection against HIV. Instead, they had unknown mutations whose consequences are unknown.

That makes us question: was this risky experiment necessary?

Moreover, did the parents know what they were signing up for?

Ethical research entails that participants must give informed consent. In He Jiankui’s case, the parents reportedly signed a 23-page document, that described the gene editing as an “AIDS vaccine development project”. The name was misleading. He Jiankui also kept his work hidden from the scientific community until he was ready to break the news. International guidelines stress the importance of scientific community discussions, transparency, and dialogue which were completely missing.

Secrecy, therefore, though important at some stage, cannot over rule scientific transparency.

Violating a Global Consensus that we should not yet proceed with heritable genome editing in humans as laid out by the U.S. National Academies and the U.K.’s Nuffield Council, sparked a global uproar. However, it also led to stricter guidelines, such as the Nuffield Councils’ guiding principles for ethical use, and recommendations for policy should “genome editing become available as a reproductive option for prospective parents.” It lays stress on individual welfare, non-discrimination, governance, public education, inclusive national and international debate before licensing on a case by case basis.

The Law

Most countries therefore, including China, the U.K., and the U.S., have legal restrictions or bans on germline editing for reproduction. In the U.S., for example, the Food and Drug Administration is prohibited from even reviewing applications for such experiments. China, after the scandal, introduced stricter laws that now classify such research a criminal act. He Jiankui was sentenced to three years in prison.

But laws are still evolving along with science, and regulations can leave loopholes. This raises an important question: How do we move forward responsibly?

Bot Thoughts

Reading about this case left me with mixed emotions. On one hand, it showed me the extraordinary power of modern science. We are now able to do things once confined to science fiction—editing the human genome, perhaps even shaping future generations.

On the other hand, it reminded me that science without ethics and law can be dangerous. Just because we can do something, the question is whether we should. Policies and laws as they evolve across nations, can be different, and need to be respected. Editing embryos is more than just a scientific act. It is also a social, moral, and legal decision. It affects not just individuals, but families, societies, and imposes its results on future generations.

As someone still learning, I have come to believe that both curiosity and caution are important attributes. And science must be guided not just by what is possible, but by what is just or justified.

He Jiankui’s case is often described as a “wake-up call.” I believe it is more than that. It is a reminder that the future of science depends on what we discover, but above all, on how we choose to use that discovery. The choice is our greatest responsibility.

References

“Genome Editing and Human Reproduction: Social and Ethical Issues – Nuffield Council on Bioethics.” Nuffield Council on Bioethics, 19 Mar. 2025, www.nuffieldbioethics.org/publication/genome-editing-and-human-reproduction-social-and-ethical-issues.

Greely, Henry T. “CRISPR’d Babies: Human Germline Genome Editing in the ‘He Jiankui Affair’*.” Journal of Law and the Biosciences, vol. 6, no. 1, May 2019, pp. 111–83. https://doi.org/10.1093/jlb/lsz010.

“Human Genome Editing.” National Academies Press eBooks, 2017, https://doi.org/10.17226/24623.

Sample, Ian. “Chinese Scientist Who Edited Babies’ Genes Jailed for Three Years.” The Guardian, 31 Dec. 2019, www.theguardian.com/world/2019/dec/30/gene-editing-chinese-scientist-he-jiankui-jailed-three-years.